FACE-POTS FROM DOVER (COVER PICTURE), KENT AND COLCHESTER

GERALD B CLEWLEY

This important vessel has not previously been published. It was found on the Burial Ground site in Dover in 1970 (Fig. 1, No.2). It is a face-jar with out-curved rim of very fine red-orange ware and with applied moulded features and a grooved handle, probably one of three. The exterior of the vessel has a grey slip and the interior a orange-buff slip. The face has arched eyebrows, stylised squinted eyes, plain nose and a pouted mouth as though he was whistling. Other types of face-pots have been found widely distributed throughout Roman Britain and especially Europe from the first to the fourth centuries. Below are references to other face-pots.

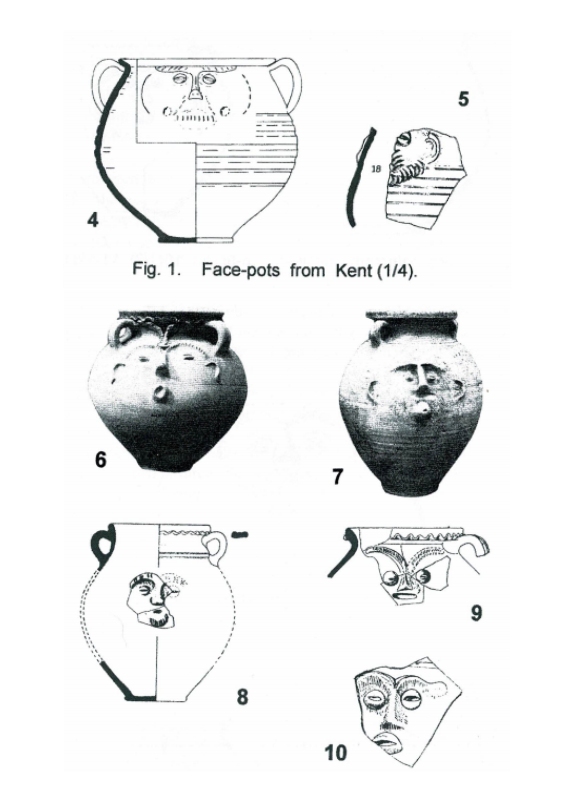

(1). The Roman Pottery of Kent (1988), R.J.Pollard, p76, fig.28, no.72, orange buff ware from East Studdal (No.4).

(2). Excavations West Kent (1973). B.J Philp, p.152, fig 45, no.420. Grey orange ware from the Roman aisled building, Darenth (No.3).

(3). The Arch. Journal (1969), Vol,CXXVI. p.98, fig.6, no.11. Redware with two or three handles (No.1), from Dover in 1913.

(4). The Arch. of Canterbury (1982), Vol, II p137, fig. 72, no.18, a face-jar in hard finely granular orange-buff ware with cream slip (5).

(5). Britannia (1975), Vol VI - 1975. p.235. S-E of Whitwell-on-the-Hill, North Yorkshire. Two pottery workshops were producing face-vases in cream ware as well as other vessels. Not illustrated.

A complete face-pot was also found at St Albans and produced in workshops there referred to as Verulamium Coarse White Slip Ware. The workshops at Colchester also produced similar vessels around the 2nd and 3rd century (6-12) ref. The Roman Pottery Kilns at Colchester (1963), M.R.Hull, p.128, fig.71, no.9. A complete face-pot was also found at Venta Silurum (Caerwent), now in the National Museum of Wales. Other sites where face-pots were found are Bodiam in East Sussex (a site with Classis Britannica tiles), suggesting that these pots may have a military connection, and also from Ospringe in Kent (see Ref 3, note 61).

These crude and rather comic looking caricatures with their funny features do not seem to have been massed produced as no face seems to be the exactly the same. For a more in depth study, see "Faces from the Past: A study of Roman Face Pots from Italy and the Western Provinces of the

Roman Empire" by Gillian Mary Braithwaite. Oxford Archaeopress,2007. After 15 years of research she produced an extensive study of anthropomorphic vases, of face-pots and other vessels of the Roman period (see chapter 9 for the face-pots from Roman Britain). Some of these vessels have been found in graves and in religious areas, especially Colchester, and it is likely that the Roman legions introduced face-pots into Britain. (NB. These vessels are also sometimes known as face-jars or face-urns).

ANOTHER ROMAN VILLA DISCOVERED IN KENT

The latest issue of ARA News (No.29, March 2013) carries the good news of the discovery of an unknown Roman villa somewhere in the Canterbury area. The discovery was made following extensive geophysical work by a combined team from the universities of Cambridge, Nottingham and Southampton. The survey suggested the likely outlines of three ranges of rooms around a probably courtyard. These were all enclosed within linear boundary ditches forming a neat rectangular enclosure. The overall pattern is a familiar one, though the complex appears to face north-east, whereas many villas face either east or south-east.

Many artefacts, including brooches and perhaps over 150 Roman coins. were removed from the site by metal detectorists between 1986 and 2002. Sadly, these remain in private collections and have not been made available to the team working on the site. More work is planned, though the exact location of the site has been withheld to avoid damage and looting.

RECOVERY OF WORLD WAR II BOMBER OFF THE KENT COAST

An exciting underwater project on the Goodwin Sands started on Saturday, 4th May, 2013 with wide television coverage. The project, undertaken by Seatech, is to lift a World War II German Dornier bomber, which was shot down during the Battle of Britain on the 26th August. 1940 with the loss of two crew and two captured. It is thought this is the only surviving Battle of Britain Dornier in the world. It is being funded through the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

First discovered in 2008 by local divers, it may take up to four weeks to complete the rescue of this very fragile plane, which has suffered from disturbance by fishing vessels as well as the usual sea erosion. Diving can only take place twice every 24 hours for up to 40 minutes during the uxton (slow tide and slack water. A special frame is being constructed and fitted around the stricken craft, some 50 feet down.

When lifted it is planned to be taken to the R.A.F Museum for conservation. At the time of going to press the results of this skilled and difficult project are unknown though bad weather conditions are likely to cause delays.

BRONZE AGE BOAT APPEAL ANOTHER £20,000!

Readers may recall the much publicized scheme to create a half-sized replica of a Bronze Age boat found in Dover during road-works many years ago. With a huge grant of £1,700,000 of European money a team of expert craftsmen built the required replica in only a few months working for the Canterbury Archaeological Trust. This was done in a field near Dover Museum. Unhappily, the attempt to float it in front of the TV. Channel Four Time Team in Dover Harbour in May this year failed (details in KAR 189, page 229). The boat started to sink because the seams had not been plugged or the wood swollen beforehand.

To cure the problem the Canterbury Archaeological Trust is now appealing for another £20,000 so that the boat can now be made waterproof and hopefully float this time.

In the meantime the first full-sized replica of a Bronze Age boat has been made by a team at Falmouth in Cornwall and successfully floated on 6th March and rowed to sea by a valiant crew. This was 15m. long, and weighed five tonnes. This was done with the University of Exeter (British Archaeology May, 2013). It is hoped that it will soon reach the Kent coast and that visitors will be able to take trips in it around Dover harbour. It is thought that Health and Safety officials may demand life-jackets or insist that the harbour be drained to a safe depth.

THE DISCOVERY OF THE LOST ROMAN TOWN OF MUTUANTONIS IN KENT

GERALD B CLEWLEY

The long-lost town of Mutuantonis is just one of 306 place-names relating to Roman Britain listed in the surviving and well known Ravenna Cosmography. This itinerary of the Roman Empire was composed by an unknown cleric in the monastery of Ravenna, around the year AD. 700, It consists of the towns and road stations covering the known world from India to Scotland in three manuscripts.

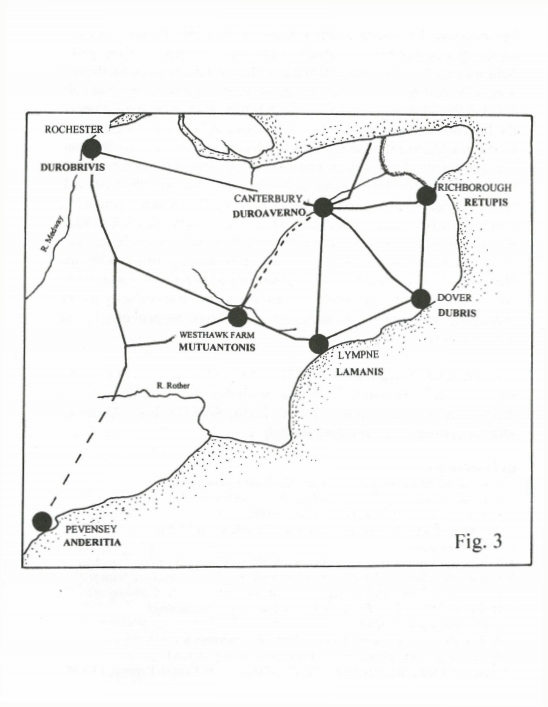

The most interesting section of the itinerary for Kent is that covering the SE of Britain. Selecting just seven of the towns from the list of those compiled by I.A. Richmond and O.S.G. Crawford (Ref. 1.) these follow a partly predictable route. In order, from the west:-

No.68. Anderelio Nubia = Anderitia, Pevensey.

- Mutuantonis (lost town).

- Lamanis = Lympne.

- Dubris = Dover.

- Duro auerno Cantiacorum = Duroaverno, Canterbury.

- Rutupis = Richborough.

- Durobrabis = Durobrivis, Rochester.

The whereabouts of the Roman town of Mutuantonis has confounded scholars for over a century; though some academics have named a number of possible places. These include Lewes, Bodiam, Hastings, Newhaven, South Malling, Beauport Park and Beddington, to name just a few. Although these places have revealed Roman artefacts and assemblages of pottery and at the very best, a Roman villa, small farmstead or even a bathhouse, this does not qualify them as being evidence of a major town complex. Importantly, when Ivan Margary (Ref.2.) was writing in 1975 the major Roman town, at Westhawk, Farm, near Ashford was unknown to anyone researching the possibly whereabouts of the lost town of "Mutuantonis".

My identification is that this newly found Roman town south of Ashford is the actual candidate for the lost town! Emergency excavations there were carried out ahead of a major housing development in fields at Westhawk Farm, just two miles south of the centre of Ashford. This was directed by the experienced field archaeologist of the C.I.B. (The Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit.) Brian Philp. FSA, the founder of Rescue Unit with over 50 years in the front-line (Fig. 1). This work discovered the actual town.

The Unit's Geophysics Survey revealed many linear features showing the predominant part of the major Roman town with probable shops flanking a main Roman road which formed a regular pattern encompassing over more than 25 acres of land. Following evidence from the Geophysics Survey, the Kent Rescue Unit excavated 23 exploratory trenches in March, 1979. The excavations uncovered remains of pits, postholes, hollows, ditches and small enclosures and most important of all, traces of rectangular timber framed buildings and evidence of iron working smelting and smithing alongside the road. This Roman ribbon development, along a major route of communication, was created shortly after the Roman conquest. Other evidence of Roman occupation included burials dating to the late 1" and 2nd century and others finds include some tile other building materials and pottery (See Ref 3).

Significantly, this site is also the crossing point of two major Roman roads described by Margary (routes 130 and 131). This intersection was located 10 miles from Portus Lemanis (Lymnpe), 13 miles from Canterbury, 28 miles from Rochester and 15 miles or more from the Weald, which was then the centre of important iron-workings. Edna Mynott's article in the next KAR (Ref 4) suggested that it resembled a frontier town. The excavation yielded over 3,000 artefacts. It is also probable that it was an important market town supplying the needs of the many iron workers in the Weald and the surrounding areas. A strong Roman presence has also been recorded in the area along the routes of these Roman roads. The Roman infrastructure of this area was of great importance for the flow of trade supplies and communications, so it is not surprising that a town was located at this intersection. More extensive excavations (by others) were later carried out across part of the Westhawk site (Ref 5).

The town lies on the eastern side of the Wealden forest of "Anderida" and near the confluence of two important rivers the Great Stour and the East Stour and its smaller tributaries the Upper Great Stour. Whitewater Dyke and Ruckinge Dyke, tributaries of the larger rivers pass just a few yards to the south of the Roman town.

My attention was also focussed on the archaeological and historical development of adjacent area in Roman times. Other Roman settlements have been discovered in the environs south of Ashford that indicate there was increasing activity at the end of the Iron Age to the time of the Roman Conquest (Fig. 2). Some of these sites are along the course of the Roman road that runs through the Roman town located at Westhawk. To the west is Brisley Farm, Stanhope, where discoveries were made of a late Iron Age/early Roman settlement (200BC to 100AD). There the course of the Roman road passes just a few yards to the north and suggests that it had some direct link to the Roman town at Westhawk, which lies at a distance of about 700m. Other occupation sites along the Roman road are at Park Wood, located south-east of Westhawk. This produced pottery dating from 100 BC to 250AD. Another site, Park Farm, produced pre-Roman and Iron Age material dated 800BC-42AD. The Roman road then passed through Bilham Farm and Cheeseman's Green, where an early Roman site has produced an assemblage of imported Roman pottery, mostly from pits, post holes and gullies. Several features were thought to date from the late Iron Age-Early Romano-British period. A similar pattern was also recorded at Waterbrook Farm, Sevington. There a dispersed pattern of late Iron Age and Romano-British features included a complex sequence of ditches, cremation burials, hut circles, pits and post holes with continued occupation from 100BC to about 400AD. Finally, at Little Chart in Stambers Field, well west of Westhawk Farm there were associated finds that include Belgic pottery, Roman coins, tesserae, samian ware, part of a Roman Bath-house and three Anglo-Saxon skeletons with iron spearheads.

My assessment of the available evidence is that the site was the main administrative centre for essential trade and commerce for the wider Ashford area. This helps establish this as the most likely place for the lost town of Matuantonis as recorded in the Ravenna Cosmography. Not only this, but this identification makes much better sense of the local order of the Ravenna Cosmography (Fig. 3). It begins at Pevensey to the south-west from where a Roman road, partly already known as far as Bodiam, could link with Westhawk (via Margary 130). The order then passes to Lympne which, as stated above, certainly links directly with Westhawk (along Margary 131). The next listed sites are Dover and Canterbury, again directly linked with each other in a very sensible order. Richborough follows, again sensibly from Canterbury, but Rochester fails to continue any obvious trend. All this greatly helps with the identification of the lost town of Mutuantonis as Westhawk Farm, in the present parish of Kingsnorth! The decline of the iron industry in the Weald may have caused the demise of the town of Mutuantonis by the fourth century.

[Quote from Margary. 1. MUTU-, if from mottu- or muttu- cf, W. mwth, "swift". This would be a suitable first element in river-names or their derivatives. 2. Santon-, cf. SANTONI, SANTONES. Meaning: 'draining strongly' or 'flooding strongly'].

REFERENCES

1.1. A. Richmond and O.G.S. Crawford. The British section of the Ravenna Cosmography. Archaeologia XCIII (1949), p. 1-50.

- 1. D. Margary. Roman Roads in Britain,(1973).

- B. J. Philp, FSA. Roman Town discovered at Ashford, KAR No.133 (1998). p.57.

- Edna Mynott. The Roman Town Ashford, KAR No, 134 (1998) p.91

- Booth P, Bingham A-M and Lawrence S. 2008: The Roman Roadside Settlement at Westhawk Farm, Ashford, Kent excavations 1998-9. Oxford Monographs 2.

- Hicks M 1993 Park Farm, Ashford. Canterbury's Archaeology 1992 (1993), p.41-2. CAT.

- Rady J. 1992: Waterbrook Farm, Ashford. Canterbury's Archaeology 1991 (1992). p.32-34. 16th Annual Report, CAT.

- Justin Williams and Nick Lester. Timber Market Town, Kentish Express, 13.8.98

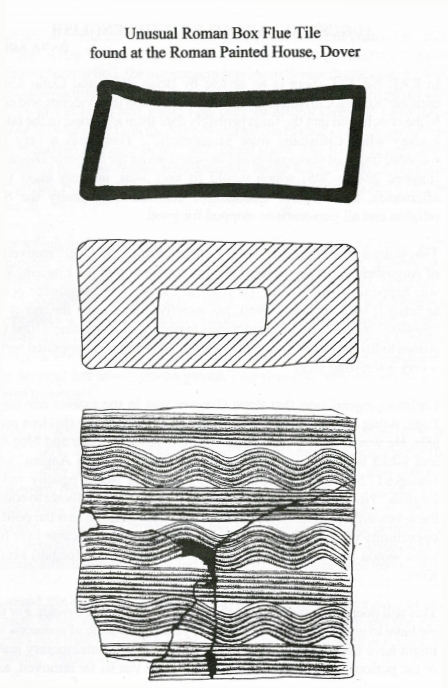

AN UNUSUAL ROMAN BOX-FLUE TILE FROM DOVER

GERALD B CLEWLEY

During the excavations carried out by the Kent Archaeological Rescue Team, under the direction of Brian Philp on the "Bingo Hall Site", Dover in 1976 an unusual hollow rectangular box flue tile was discovered. This came from a demolition layer in the hypocaust system of a heated Roman building at the N.E. corner of the "Roman Painted House". This near complete example of a large box flue measured 29cm in length by 28cm in width, by 13cm in depth. It was decorated with combing on the upper and lower sides, which consisted of alternating wavy and horizontal lines the lapping showed that this was applied with a seven-toothed comb starting from the right and working across the face of the tile. The combing allowed mortar and plaster to adhere more easily to its surface.

Tiles of this nature are found in the construction of Roman bath-houses suites and also the heated rooms of villas. The hot air passed under the floor and then up vertical flues "tubuli" in the walls and corners of the room to the roofs, some vaulted. They were an integral part of a hypocaust system.

Box-flue tiles are known at several different sites in Britain with similar combing designs, but these tend to be smaller The box-flue tile from the Roman Painted House with the Bacchic Murals at Dover (Ref.1, p.100, Fig. 38, No 277) measured 41cm in length 14.7cm in width 10.5 and (No 278) 31.5in length by 16.5 in width. Other examples come from Fishbourne (Ref.2 1961-1969) and from Reculver (Ref.3, p.191, Nos.479 and 480).

References.

Ref. 1. The Roman House with Bacchic Murals at Dover (1989).

Ref. 2. Fishbourne Excavations (1971)

Ref. 3. The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent (2005).

ROMAN TEMPLES AND SHRINES IN KENT

GERALD B. CLEWLEY

Roman Britain contained many temples of various forms, but predominantly of the Romano-Celtic type. This consisted of a central room, or cella, enclosed by an ambulatory (veranda) on all four sides. Some temples may have been enclosed inside a temenos (sanctuary area). Several temples are known in Kent and those listed below now form the latest study. Part I is here and Part II will be in the next KAR together with the discussion.

- Richborough Settlement and Fort. In 1926 the construction of the east Kent Railway revealed two Romano-Celtic temples 350 yards south of the Roman fort at Richborough (Rutupiae). Each had a rectangular cella enclosed by an ambulatory (Ref.1).Temple 1.

The northerly of the two was slightly the smaller, the ambulatory measured 40ft. x 39ft. with the cella 13ft. sq. The ambulatory varied in width from 5ft. to 7ft. and the surviving walls were 6in. to 3ft. high with a thickness of about 3ft. The foundations were of water-worn flints set in clay and above this the walls were constructed of rough chalk blocks set in pink mortar containing pebbles and lumps of chalk.

Temple 2.

The ambulatory measured 43ft. x 46ft. with a cella 15ft. 6ins. x 17ft. The outer walls were 3ft. 3in. to 3ft. 11in. thickness, the cella walls being 3ft. to 4ft. thick. Pitts cutting into temple 1 contained coins of the fourth century so the temples may date from the 2nd-3rd centuries.

- Boxted, near Sittingbourne.

Only the foundations of this Romano-Celtic Temple survive, built of flint (Ref.2). It was discovered 300 yards. south-west of the corridor Villa at Boxted. Only the western half was excavated, here a concentric square with a portico and cella. No floors were located and a possible votive pit was found inside the cella. No dating evidence survived.

- Worth, near Sandwich.

The Romano-Celtic temple at Worth was discovered in "Castle Field" in 1925 (Ref. 3), having been seen as a crop-mark before. The excavation revealed a rectangular structure constructed of chalk blocks set in a lime mortar standing on a foundation of chalk rubble to a depth of about 8ins. The walls survived to a height of 2ft. The width of the outer wall of the ambulatory was between 3ft. 3ins. to 4ft. in thickness and the inner walls of the cella were 4ft. to 4ft. 7ins. width. The space between outer walls and the inner walls varied between 7ft. 8ins. to 8ft. 6ins. There was some evidence of a rough chalk floor on the portico with the cellar having a floor consisting of broken tile and chalk. It had been suggested that the temple may have been dedicated to the Goddess Minerva. Objects found include fragments of Roman pottery, a piece of a statue (right hand grasping a spear) and a coin of Constantine II 337-40 from the floor of the cella..

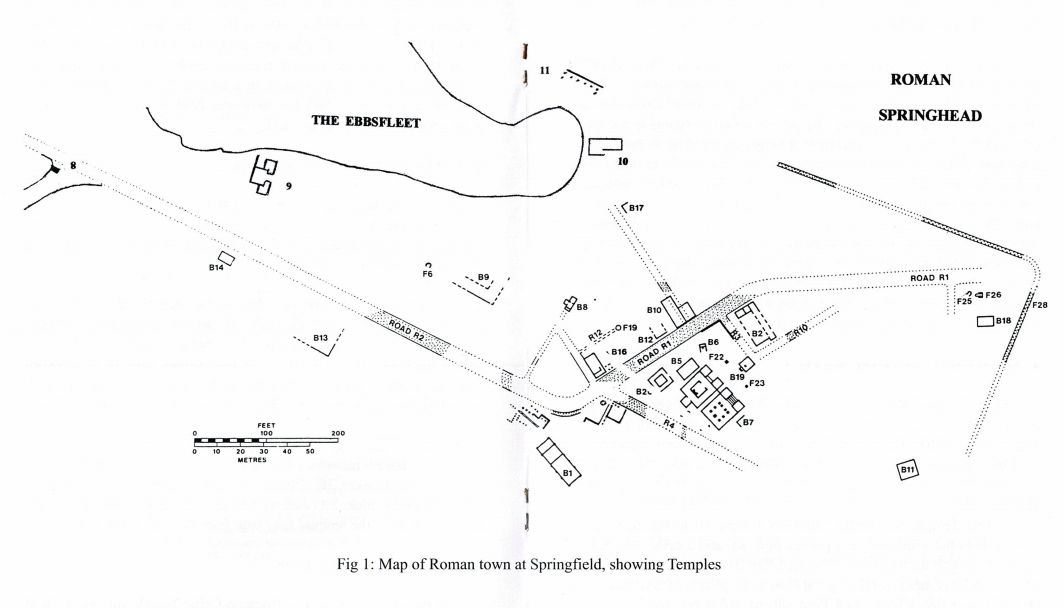

- Springhead (Vagniacac). see Fig. 1.

At least 11 temples have been found at Springhead, seven excavated by Syd Harker and Bill Penn and these are listed in their order (B3-7 and B19 and B20). Four more were much later discovered ahead of road-improvements associated with the Highspeed Railway (Nos.8-11)

Temple 1(B3)

This Temple was located between Temple III to the north and Temple II to the south; it had a portico 36ft. sq. and a cella 18ft. 8ins. sq. (Ref. 6) with all the walls of bonded flint 21ins, wide. Built about AD 90 this structure went through at least three phases of construction. During phase two a tessellated floor surrounded a geometric mosaic, covering an area of 16sq. ft., A mosaic in the porch was 26ins. by

54.5ins. an area of 7 sq. ft., The vestibule also had a mosaic and this covered an area of 64 sq. ft. It appeared that the walls may have been plastered as an abundance of plaster was found lying on the floors in the cella and vestibule. It was in use to about AD 350. A fine stone altar and base was found inside the temple, un-inscribed but decorated.

Temple 2 (B4)

This Temple had roughly the same dimensions as Temple 1 and was separated from it by only a few feet. The structure was built on a chalk raft 14 -21 inches in thickness and was probably covered by a tessellated floor. This surrounded the cella, with eight column bases and at the west end a statue base made of tiles (Ref.7). In the pebbled courtyard, opposite the entrance, stood an altar base (Ref. 8, p.112)

Temple 3 (B5)

This was a simple rectangular structure 28ft. x 19ft. 4ins, located north of Temple 1. The exact purpose of this building has yet to be established, for there was no well-made floor, doors or statue base, bu had thick walls lined with opus signinum, but little plaster (Ref. 9),

Temple 4 (B6)

A rectangular structure 12ft. 4ins. x 7ft. 7ins. the foundations of which were made up of loose flints supporting a wall of chalk blocks (Ref 9. p.118). It was divided by a cross wall to form a south room 7ft. 7ins. sq room which had the remains of a tiled base for a shrine (plate IIB) and also a small rectangular room with a floor of rammed chalk. This had wall plaster with painted geometric pattern in situ (Ref. 9 p120). This was probably a road-side shrine..

Temple 5 (B7)

Only part of this structure was excavated as the rest lay under the Railway Embankment. The main part consisted of a small room 15ft. 8ins. x 10ft. 9ins. and walls 16ins. wide and plastered internally (Ref.7, p.117). Over the floor of the Temple was layer of plaster rubble on top

of which was found a hoard of eight coins of similar date ending at AD 375. Nine inches away was found another group of 4 coins and further away another group of 4 coins and then two groups of three a total of 22 coins. It has been suggested that the coins were attached to the wall of the temple in small bags and had eventually fallen to the floor (Ref. p.119). Other interesting finds of significance were three face urns, six bracelets, some small beads and a large votive pot (Ref.7, p.10).

Temple 6 (B19)

Gateway or temple. This building also lay inside the temenos area. The robbed walls were three to four feet wide and steps lead down to a temple courtyard and an altar or statue base in front of a votive pit containing two animal burials and 25 coins (undated).

Temple 7 (B20)

The report for this temple was ongoing, the plan of which is a rectangular portico with a rectangular room at its centre. This is similar to the one at Worth. No other details available.

Temple 8 (Shrine)

Interpreted as roadside shrine by Wessex Archaeology it overlay a mettled surface on the north-west edge at the junction with Watling Street. Rectangular in shape, about 3.3 m. x 2.6 m., with no evidence of a foundation-trench, but just chalk footings. Within the structure were 17 coins spanning AD 260-402 (Ref 12, p.89).

Temple 9

Wessex interpreted this building as a Temple enclosed by a fence identified as a temenos of late-second century date. It was aligned NE to SE at right-angles to Watling St. and only 5 m. from the Ebsfleet to the NE (Ref.12, p.94). The walls survived to about 0.50m. above ground-level, built of flint nodules and chalk set in a lime mortar. substantial amount of roof tile was found associated with the building The vestibule measured 2.35m. sq. with doorways on three sides. Th threshold of the vestibule had two shallow steps of irregular slabs of

Kentish ragstone (Ref.12, plan p.95) and within it was a tiled floor, each tile .25cm. sq. On either side of the vestibule were two L-shaped rooms, the NW room having the remnants of painted plaster in situ. The whole structure had at least 5 rooms (Ref. 12, p.95, fig.2.67).

Temple 10

Facing the head of the Ebbsfleet, only 5 metres from its edge, was another rectangular temple the central part of which measured 13.5m. x 5.0m. It had six pairs of flint and mortar foundation-pads along the foundation trench each 1.00m. x 0.60m. and 0.80 deep and also another pad at each end. Plaster was also found associated with this building (Ref.12, p61, plan 2.42).

Temple 11 (Portico Structure)

Wessex identified this as a Portico, but more investigation is needed to establish that this structure was a temple, or not. The evidence so far to support this is that the Portico Structure (Ref. 12, p.69 plan 2.41) was defined by a 19m.long wall, still 0.45m. high and 0.45 m. in width, constructed of flint and chalk rubble. West of this was a row of six post holes with another at each end. Associated pottery was dated to the late-2nd and early-3rd century.

References

|